The trailblazing women who moved mountains

The worn paths of the Lake District’s most popular walking routes are an obvious reminder of the many boots that have gone before. An exhibition in the heart of the Lakes this autumn reflects on how some of these feet travelled more than 200 years ago – and were female.

This Girl Did: Dorothy Wordsworth & Women Mountaineers, nowon at the Wordsworth Trust in Grasmere until Christmas, celebrates the women walkers whose hikes and climbs represented more than a bid for fresh air or, in the days of limited transport, a way to get from A to B.

The exhibition, designed and written by Melissa Mitchell of the Wordsworth Trust, Dr Jo Taylor and Professor Paul Westover, applauds them as pioneers who challenged social convention; their treks, whether in search of solace or excitement, symbolic of their independent spirits at a time when ladies were not expected to engage in strenuous activity.

For Dorothy, sister of one of England’s best loved poets William, walking was a necessity but also a pleasure, her frugal side also mindful that it cost nothing.

“It not only procured me infinitely more pleasure than I should have received from sitting in a post-chaise – but was also the means of saving me at least 30 shillings,” is a quote from one her letters.

The exhibition shows that walking was very much a normal, daily activity for Dorothy, with a typical morning starting at 6am followed by “walking with a book until 8.30”. She might then walk from Grasmere to Ambleside to collect the post or wander in the valley.

After tea the Wordsworths would walk together until 8pm and then Dorothy would head out again later, alone, enjoying one of her favourite twilight or moonlight strolls.

“Unless you have accustomed yourself to this kind of walking you will have no idea that it can be pleasant, but I assure you it is most delightful,” she wrote.

Dorothy, however, was much more than just a garden stroller. Along with her brother, they thought nothing of walking from Grasmere to visit friends Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey in Keswick and in 1803 she, William and Coleridge embarked on a 663-mile journey through the Scottish Highlands, mostly on foot.

She was obviously fit too, able to cover 16 miles in four-and-three-quarter hours “on a blustering cold day without having felt any fatigue” aged 46. Perhaps she was in training for her greatest feat – scaling Scafell Pike in 1818. At 978m or 3,210ft, the peak had been declared the highest mountain in England in 1790, a title of which Dorothy must have been aware, although it was not yet on the tourist trail.

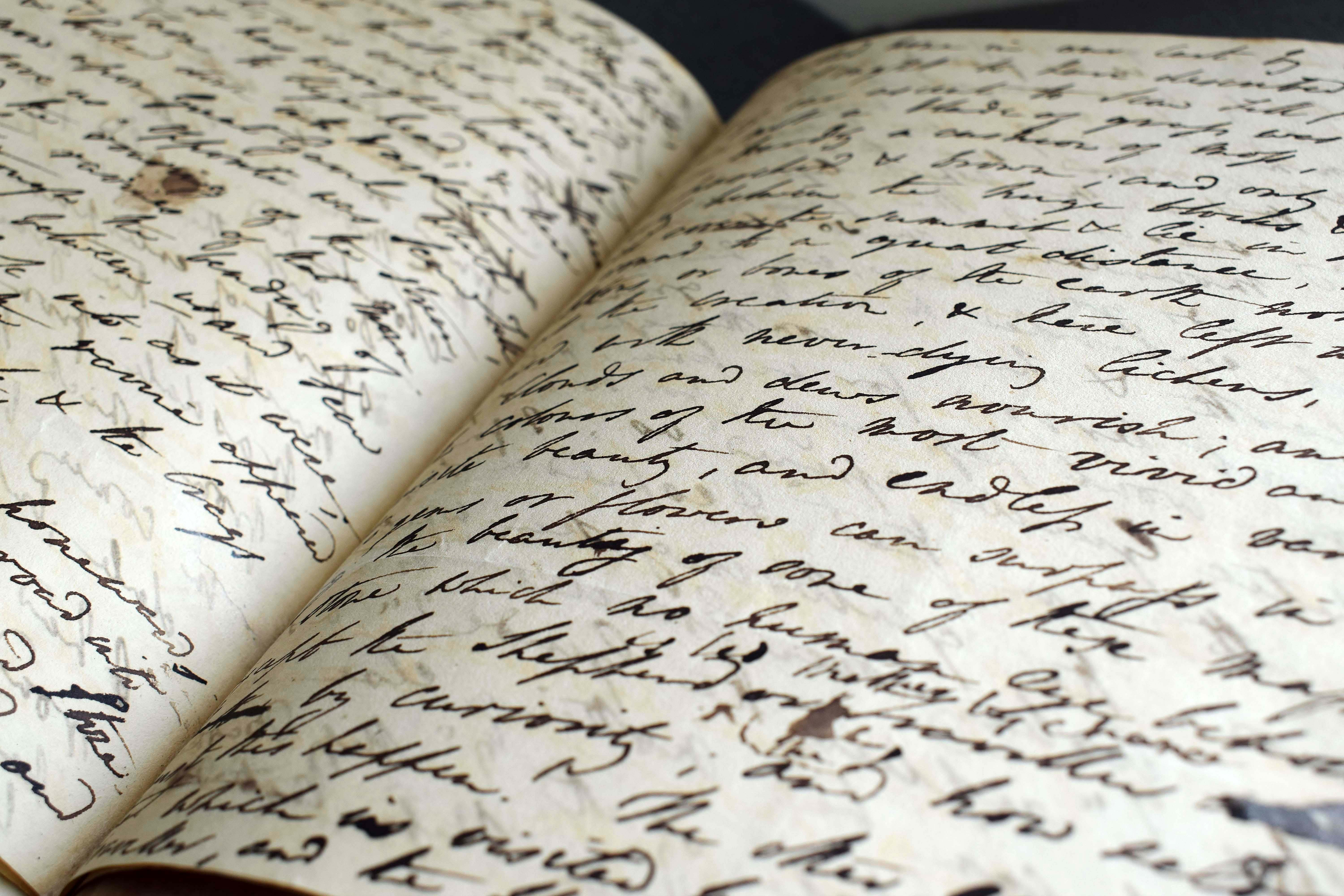

She set out to conquer Scafell, an “uncommon performance”, with a friend Mary Barker, 44, on October 7, 1818, along with a guide, a porter and probably a maid, taking food wrapped in paper – it’s suggested their picnic comprised savoury pudding, cold pancakes, cheese, bread and water – as well as ink quills and paper. The four-mile ascent ended with a considerable vertical climb, but their “courage did not fail” declared Dorothy.

Thankfully, it was a fine day and they enjoyed clear views on reaching the summit. As one of the exhibition authorspoints out, in the days before high rise buildings and flight, witnessing the view from such an elevation was a rare thing indeed.

At the top they wrote a letter to an eager mountaineer friend Sara Hutchinson, the younger sister of Dorothy’s sister-in-law Mary Wordsworth (Coleridge, who himself had climbed Scafell in 1802 had fallen in love with Sara in 1799).

Dorothy’s account of the ascent was included, without attribution, in William Wordsworth’s 1822 Guide to the District of the Lakes, it being assumed that he had completed the ascent and leaving readers unaware that it was actually Dorothy who had claimed the peak. It was, however, recorded in copies of her own accounts, her and Mary’s achievement being the earliest record of an ascent of the mountain by women.

It undoubtedly inspired others to scale Scafell, including Harriet Martineau, a friend of Charlotte Bronte, in 1855, and Eliza Lynn Linton, the first salaried journalist in Britain, in 1864, who said it was “more formidable than ever”. It’s noted that by then Scafell was an accepted yet challenging route for woman to undertake.

Sadly, well before this time, an infection – ironically caused by “imprudent exposure during a long walk” – had ended Dorothy’s walking days and she spent her later life being pushed around the garden in a bath-chair. Her memories of walking provided some solace for her, however, as she described in a moving poem Thoughts on my Sick-Bed:

No need of motion, or of strength,

Or even the breathing air;

- I thought of Nature’s loveliest scenes;

And with memory I was there.

Perhaps inspired by her aunt, William and Mary’s eldest daughter Dora Wordsworth climbed Helvellyn with her father and her husband Edward Quillinan. Although her ascent was on horseback she completed it despite – perhaps because of – being told that no lady had ever done it before.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s daughter Sara walked the fells and countryside around Derwentwater and Bassenthwaite, referencing them in her poetry.

Ahead of all these intrepid ladies, however, was Ann Radcliffe who rode up Skiddaw in 1794, and Sarah Murray, whose 1799 guide book contains some of the earliest accounts of caving as well as being a rare early example of a woman fell-walking and a travel guide (she reviewed inns along her routes). In 1801, she became one of the first women to ascend one of the Cairngorms on horseback. She recorded the spectacular views from Honister Crag but was less than impressed on reaching the summit of Skiddaw – “hardly worth the fatigue”.

Helvellyn via Striding Edge was claimed by Hannah Gurney in the early 1800s, shortly after forgoing the pull of Bath society to become a Quaker minister, a role which took her to the Lakes. Her cousin Elizabeth – who later became Elizabeth Fry – came to the Lakes in 1798 on an extended visit and also found the clarity to follow her calling: “I know now what the mountain is I have to climb,” she wrote.

In recognising these women’s achievements it perhaps inevitable today that we view them as an enormous step on the journey towards equality and the fight for female emancipation.

For the trailblazing women themselves the motivation to climb a mountain might have been simply because it was there. And because they could.

* ‘This Girl Did’: Dorothy Wordsworth & Women Mountaineers is on until December 23. https://wordsworth.org.uk